When President Donald Trump reinstated the Mexico City Policy last January as one of his first acts in office, advocates for women’s health were alarmed. The policy, better known as the Global Gag Rule, cuts off US funds for programs overseas that are involved in abortion-related activities, including counseling and informing women about their reproductive choices. This restriction is literally a “gag” on health care providers worldwide, even in countries where abortion has been decriminalized.

Historically, the Global Gag Rule has been enacted in the US via executive order by every Republican president and rescinded by every Democratic president since it was first introduced in 1984. But this time is different.

The Trump administration has expanded the policy to apply restrictions on all US-funded global health assistance, not only aid to organizations involved in family planning. In practice, this means that if an organization provides information, referrals, or services related to safe abortion care, they will no longer be eligible to receive US aid for HIV or tuberculosis treatment, contraception services, mother and child health care, nutrition programs, malaria treatment, or any other care. This massive expansion of the policy sent shock waves across the global public health community, including here at Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).

The rule has nothing to do with US funding for abortions–the government made it illegal to provide funds for abortion internationally with the passage of the Helms Amendment in 1973. The policy’s intent is to censor discussion of abortion in any context—even if non-US funds are used for those discussions. The new version of the policy effectively influences what care providers do with funds from other donors.

Many organizations face a difficult dilemma: either to continue with their abortion-related activities and risk losing vital US funding, or to drop these critical services to comply with the policy’s restrictions. Some organizations cannot afford either option and may have to shut down.

The expanded Global Gag Rule threatens progress on many fronts, from efforts to reduce mother-to-child transmission of HIV to global immunization campaigns. The impact is also greater now because the US has become the largest funder of global health programs worldwide. Between 2006 and 2017, US spending on global health more than doubled from $4.1 billion to $9.7 billion, according to public records.

At MSF, we believe that women should have information and access to services that protect their health and wellbeing. We know that unsafe abortion is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality worldwide—responsible for up to 13 percent of all maternal deaths in recent years, according to the World Health Organization. The vast majority of unsafe abortions—a staggering 97 percent—occurred in developing countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

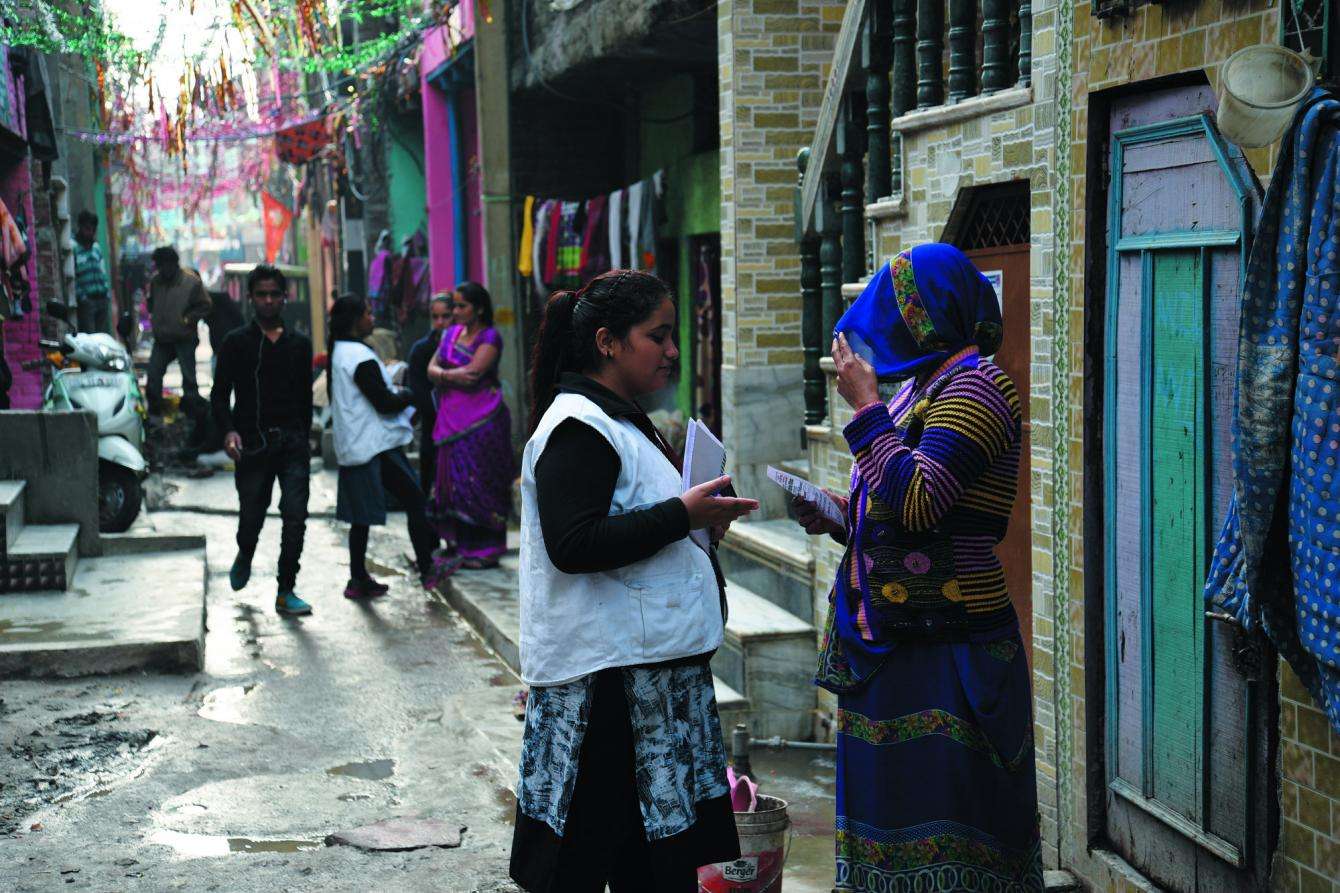

MSF teams treat patients for complications from unsafe abortions every day across our projects, including in war zones and refugee settlements. And we provide termination of pregnancy to women and girls who request it; both services are part of our strategy to reduce maternal mortality and suffering where we work.

The policy’s intent is to censor discussion of abortion in any context—even if non-US funds are used for those discussions.

Since MSF is funded independently and receives no money from the US government, the Global Gag Rule does not affect our ability to continue providing care where the needs are greatest. But in the international aid world, MSF is an exception.

Catrin Schulte-Hillen is a midwife and the head of MSF’s sexual and reproductive health care working group. In this interview, she explains how women and girls, as well as entire communities, could be harmed by the latest imposition of the Global Gag Rule.

What are some of the immediate consequences of the new Global Gag Rule?

Unsafe abortion has always been notoriously under-addressed, but since the 1995 UN Conference on Women, the international community has begun to recognize it as a public health issue—as it is one of the top causes of maternal mortality. And that it needs to be addressed, through the prevention of unwanted pregnancies—with contraceptive care—and through the prevention of unsafe abortions—through access to safe abortion services. If health providers agree under pressure from the US not to speak to patients about safe abortion care as one of their options when faced with an unwanted pregnancy, this just strengthens the status quo of restrictive laws and far too many maternal deaths.

For some organizations this is extremely painful. They’ve been working for years to help women access sexual and reproductive health services and to reduce maternal mortality. For others—organizations, or individuals in their leadership—the policy could provide a perfect excuse not to push for the provision of safe abortion care.

The bottom line is that the very limited access to safe abortion care that exists is going to be further compromised. And to me it's even worse that women will not have access to complete information about their health options. They will be stuck again with this silence and stigma surrounding abortion. Even when going to the health provider, a woman will face the taboo: “I can't talk about this.” Not because of social norms but because of financial restrictions linked to US policy. A woman will be unable to talk about her pain, her struggle, and she will no longer feel like she has someone on her side who doesn't judge her.

As a midwife, what worries you most about these restrictions?

As a midwife, the most disturbing thing about this to me is that the policy basically asks medical personnel or medical organizations to work in a way that is not in line with medical ethics. Medical ethics require that patients have full insight into their treatment options and that you give patient-centered care, which includes providing all the objective information that allows them to make an informed decision.

For the largest health funder in the world to say, "You can't talk about abortion. You can't give information about it. And if you do, then we will punish you by not supporting any of your activities…." That's pretty radical.

It’s worrying because it’s impossible to separate the act of counseling or referring patients from all the other aspects of women’s health care: providing contraception, treating sexually transmitted infections, giving guidance on birth spacing. You can’t just take one piece out and say, “You can’t talk about it.” This is what we in women’s health care mean when we talk about the continuum of care—all of the pieces of women’s health are interconnected. Women should be able to get complete reproductive health care from their medical provider.

And what kind of example is the US setting? The US is saying, “We don’t care about medical evidence. This is what we want, so do it.” How can the US then say to another country that they should make decisions based on needs and public health concerns?

MSF does not receive US government funding, so how are we affected?

Directly, we are not affected. And in many places where MSF works, we are the only ones providing medical care, so we might not see a major difference. However, in other places where there have been projects funded by US programs I think we will find providers shutting down, leaving us even more alone than before. This could be most significant where other organizations have been providing family planning services, including contraception, and a lack of access to contraception could lead to more unwanted pregnancies. Groups that have been referring women to safe abortion services or providing this care themselves are likely to stop all of their work rather than accept the policy, which could lead to an increase in unsafe abortions and the medical complications and the deaths that come with that.

So, indirectly, we could be affected because our colleagues are affected. Their ability to respond to a variety of health challenges will be compromised. And we will all lose out on a chance to push for women's health and reduce maternal mortality.

What are the sexual and reproductive care services that MSF provides at its projects?

MSF has developed all of its activities under the umbrella of reducing mortality and suffering, particularly for vulnerable people affected by crisis and conflict. Our reproductive health care activities fall into two groups: reproductive health care and sexual violence care. For the first group of activities, we focus on having a direct impact on mortality. The periods immediately before, during, and after birth are when most women and babies die—thus the importance of skilled birth attendance to prevent and manage the main complications: namely bleeding, infection, hypertensive disorder, and obstructed labor. We provide postnatal care during the potentially risky weeks after birth.

The treatment of abortion-related complications also has a direct impact on mortality. Women and girls come to our facilities with uncontrolled bleeding, trauma, and infections from non-medical attempts to abort. And, finally, we offer safe medical care for termination of pregnancy to prevent unsafe abortion.

We have additional preventative activities that contribute to reducing mortality and suffering: contraception, the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, and screening for cervical cancer. To lessen women’s suffering we also provide repair for obstetric fistula.

Treatment for sexual violence, which affects men and boys as well as women and girls, is designed to reduce short- and long-term consequences, primarily of rape. We provide medical care for physical injuries, preventive treatments for infectious diseases, prevention and management of unwanted pregnancy, and mental health support. We also provide victims with a medical legal certificate that could one day help them seek justice and compensation.

What are some of the biggest challenges associated with providing sexual and reproductive health care in the places where we work?

The most challenging part of providing this care is ensuring that women have access to it. And that depends on how much value the community, the husband, the society, gives to a woman’s health status. That can be the biggest barrier. Will a man pay for transportation so his wife can have antenatal consultations? Will he allow his wife out of the house to go to the hospital to deliver? Do women have decision-making power over the use of contraception or receiving a Caesarian section?

The other challenge, particularly with sexual violence care, is getting the information out there so people will come. To overcome the stigma and taboo and the risk of being discovered and exposed, victims need to see the added value that medical care has for them. They will only take the risk if they understand that medical care can help prevent further suffering, whether it’s HIV/AIDS, syphilis, or unwanted pregnancy.

The challenge is in knowing how to get the messages out in the right way. It’s a much more refined message because it has to do with sex and power relations and crime. You always want to reach out to the victim, but you don’t want to expose them, because there might be very negative repercussions if they are exposed.

Stigma, taboo, and the lack of value given to women’s lives all help keep them from getting the care they need, across the board. The new version of the Global Gag Rule will only make these forces even stronger, and that is extremely worrying.