Severe overcrowding and chronic health gaps are placing enormous pressure on providers in Dadaab

Crowded into camps built to house 90,000 people that are now "home" to more than 300,000, Somali refugees in Dadaab, Kenya, urgently need additional assistance and more shelter.

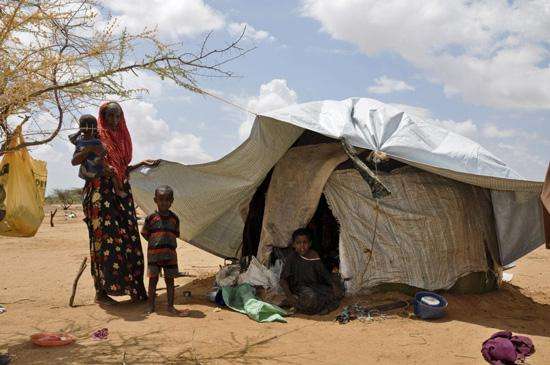

Kenya 2011 © Nenna Arnold/MSF

A newly arrived family of refugees from Somalia stand outside their shelter, near Dagahaley refugee camp, Dadaab, Kenya.

Stranded in the deserts of northeastern Kenya, surrounded by mile upon mile of sand and scrub brush, 30,000 people are living in makeshift shelters under a burning sun. They had crossed the border from neighboring Somalia, 80 kilometers [48 miles] away and headed for the refugee camps of Dadaab. But the three camps there are already full, and there is nowhere for them to stay.

The refugees, most of whom are women and children, arrive with no money, no food, no water, and no shelter, but it takes, on average, 12 days for them to secure their first rations of food and 34 days to get cooking utensils and blankets from the United Nations refugee agency that runs the camps. Until then, they have to fend for themselves in a hostile environment. Seeking sanctuary from the relentless heat, the pervasive dust, and the hyenas that prowl the area, they've erected fragile shelters in the surrounding desert, tying together branches or brushwood to form domed structures which they cover with cardboard, polythene or torn fabric.

A City-Sized Camp

The camps of Dagahaley, Hagadera and Ifo collectively form the largest refugee camp in the world. Built two decades ago, they were designed to house up to 90,000 men, women, and children who had fled Somalia’s civil wars. Today, with no end to the conflict in sight, there are more than 350,000 people crowded into the camps and the surrounding areas.

New arrivals are surging as well. Some 44,000 more refugees have already been registered in 2011. By the end of 2011, the population needing refuge in the camps is projected to reach 450,000, which amounts to more people than live in metro Miami or Atlanta.

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins San Frontières (MSF) has worked in the camps at Dadaab for a total of 14 years. Since 2009, MSF has been the sole provider of medical services in Dagahaley camp, providing health care for the camp’s 113,000 residents at five health posts and a 170-bed general hospital.

It is extremely difficult for health providers to keep up with demand, however. As the camps and the surrounding desert grow increasingly crowded, living conditions are worsening and the availability of essential services like water, sanitation, and education is shrinking. A planned extension to the Ifo camp would have created shelter for an additional 40,000 refugees, but a breakdown in negotiations between Kenyan authorities and the UNHCR has stalled construction.

“Nothing But The Clothes We Were Wearing”

Mahmoud arrived at night with his wife, five children, and widowed mother. They are staying with his sister in the desert shelter where she has been living for the past three months. “Our journey took nine days," he says. "We brought nothing with us but the clothes we were wearing. In Somalia, we were farmers, but all of our animals died in the drought. While there was no fighting in our town, a group of militants were in control and were demanding that we pay them taxes. I couldn’t pay, and that’s why we decided to leave. I was terrified of being stopped on the journey and being preventing from crossing into Kenya. On the way, we had to hide.”

Most refugees arrive at the camps in poor physical condition. The borderlands are a lawless, dangerous place, and many people encounter violence, extortion and harassment as they travel through. What's more, the majority of people in Somalia, where the health system is in a state of near-collapse, have lived without conventional medical care for years. And a drought has worsened the health situation.

The pressure on health services providers is mounting. “We are already at bursting point, but the figures keep growing,” says MSF nurse Nenna Arnold. “This situation is a humanitarian emergency.”

Arnold and her team of 78 Somali health workers are in charge of monitoring the health needs of the new arrivals. Every day, they go out into the camp and the surrounding area to find people who need treatment. The sickest—including a large number of children with moderate and severe malnutrition, often with medical complications—are driven straight to one of MSF’s health posts or to MSF’s general hospital in Dagahaley camp.

No Vaccinations, Wards Crammed With Beds

MSF is rushing to bring in additional staff and resources as the population expands. Last month, staff at the health posts gave 11,963 consultations, many of them for patients suffering from respiratory tract infections, diarrhea, tuberculosis, malnutrition, and trauma, as well as an increasing number of complicated cases. A new health post in the middle of the new arrivals’ area opened in March and is already doing an average of 110 consultations a day. MSF has taken on more than 50 extra staff since October, bringing its total number of staff in Dagahaley camp to 458.

Two of every five newly-arrived children have never received any vaccinations. This, combined with their nutritional status and poor living conditions, represents a major health threat. Flash vaccination campaigns, some held in the desert under the shade of a tree, help to forestall outbreaks of disease.

MSF’s 170-bed hospital in the middle of Dagahaley cam is the only functioning hospital for the 113,000 refugees in the camp and in the desert. Dr. Gedi Mohammed, the hospital’s director, says, “Until recently bed occupancy was 80 percent on average, but with the new arrivals, we are now seeing occupancy rates of 110 percent." This means that some patients, at times, must share beds.

All services are being stretched. Births in the maternity ward have doubled compared to this time last year, with 308 deliveries in the past month alone. Many of the new arrivals are traumatized by their experiences, and the mental health program is thus busier than ever, with 964 patients receiving mental health support in the past month.

The inpatient therapeutic feeding center for severely malnourished children is so full that tents were set up in the hospital grounds to accommodate them all until a new 60-bed extension ward opened in May. Eighty malnourished children receive inpatient care, and 782 received outpatient care. The supplementary feeding program provides more than 7,000 families with extra food.

While MSF continues to try to scale up its medical response, what is needed is real movement to house these desperate people in humane conditions, in proper shelters with access to the basic needs of life, including water, sanitation, food, and security.

MSF has been providing medical care in Kenya since 1992, and has worked in the camps at Dadaab for a total of 14 years. Since 2009, MSF has been the sole provider of medical services in Dagahaley camp, providing healthcare for the camp’s 113,000 residents at five health posts and a 170-bed general hospital.