MSF first started HIV/AIDS prevention and control activities in Malawi in 1994, beginning in the district of Mwanza. Three years later, projects were extended to Chiradzulu, an area where an estimated 20 percent of adults were HIV-positive.

In August 2001, MSF started a program to provide free access to anti-retroviral therapy (ART) at Chiradzulu district hospital. Before then, HIV treatment was not available in the country and medical action was limited to prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections. That same year, an estimated 86,000 people died of AIDS-related causes in Malawi, according to UNAIDS.

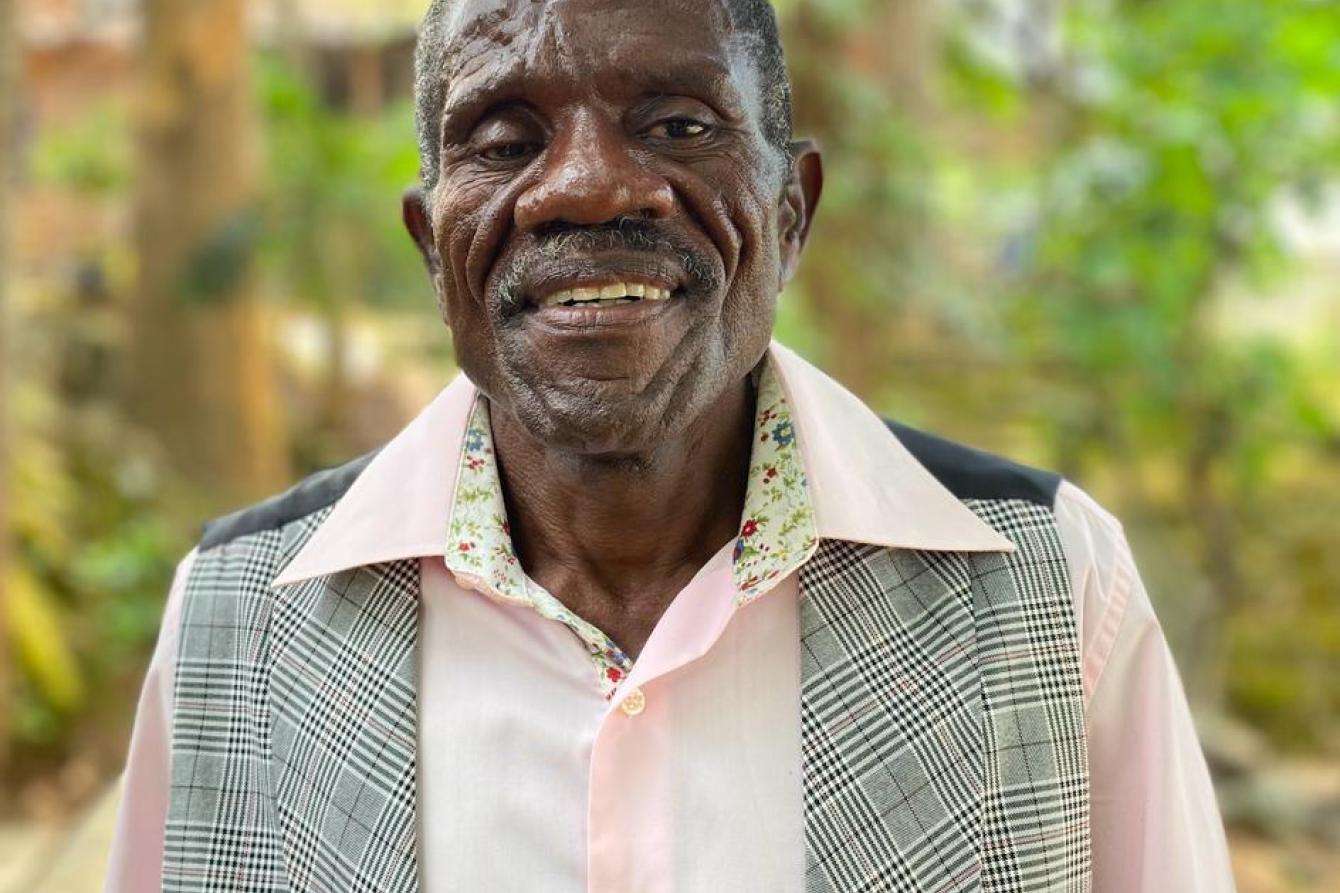

Fred Minandi, a retired farmer, proudly recalls that he was the fourth patient to receive ART from the Chiradzulu project. It was August 16, 2001, and he was 41.

“In 1999, I went for an HIV test at Chiradzulu district hospital. I was not working anymore because I was too sick and had been suffering from opportunistic infections since 1997. I tested positive. Later, I met with MSF counselors who told me they were going to begin ART. I was lucky to be one of the first patients to receive treatment. After a month, I was able to start work again.”

Streamlined care and access to medication helped patients and reduced transmission

The project in Chiradzulu proves it’s possible to tackle HIV in poor rural settings and that patients can and will keep up with a strict HIV treatment regimen—an idea that was initially met with significant cynicism by some health workers and authorities. The project set a precedent that has helped pave the way for advocacy for cheaper drug prices and to ensure access to ART in low-income countries.

In July 2002, Fred was invited to speak at the 14th International Conference on HIV/AIDS in Barcelona, where MSF’s presentation, “Access to ART in MSF programs,” included the Chiradzulu experience.

“If I am here to talk to you about [ART] today, it’s because I am receiving treatment,” said Fred in his address. "Some of you will say that Africans cannot take medicine properly because we don’t know how to tell time. I don’t have a watch, but I can tell you that since I began my triple therapy, I have never forgotten to take a single dose."

By the end of 2003, more than 2,000 patients were on ART as part of the Chiradzulu program, where 200 patients a month were responsive to treatment—comparable to the statistics in higher-income countries.

As the years went by, a number of factors made it possible to expand access to ART, including simplified treatment approaches and decentralized care through peripheral health care facilities. Advances in treatment strategies also allowed patients in stable condition, and who had been on treatment for at least a year, to have medical consultations once every six months as opposed to every two to three months. This six-month appointment (SMA) system helped make treatment easier for both patients and medical staff.

By 2009, every health structure in Chiradzulu district was able to provide a range of services for HIV/AIDS patients, such as testing, prevention of mother-to-child transmission, and treatment for patients co-infected with tuberculosis.

In 2013, an MSF study in Chiradzulu showed that 65.8 percent of people who needed ART were receiving the appropriate medicines, and a population-based survey revealed that there was also a very low level of new infections (0.4 percent), suggesting that the large-scale provision of HIV treatment had played a role in reducing transmission.

Such progress was not only made possible by the partnership between MSF and local health authorities but by the patients themselves. Patients like Fred formed support groups and were employed by MSF as peer care counselors to encourage others to get tested and empower them to stay on their treatment.

Addressing the unique challenges faced by children and teens living with HIV

While people living with HIV face many of the same issues regardless of their age and circumstances, children and teenagers face specific challenges that require dedicated care. For children, even simply explaining what it means to be HIV-positive and how it can impact a person’s life can present challenges. Other patients might struggle to come to terms with the fact that they have a sexually transmissible illness before even reaching their own sexual maturity.

In 2017, MSF began Saturday "teen clubs" offering HIV care, follow-up, sexual and reproductive health services, and psychological and social support to teenagers living with HIV. These clubs provided a safe, friendly space where they could also benefit from peer support. Attendance was linked to a patient’s overall well-being and their adherence to treatment.

For many young patients, attending a teen clubs helped them in the transition from being overwhelmed by a condition they struggled to make sense of, to being better prepared to tackle it. In 2019, as many as 9,200 teenagers attended teen clubs in Chiradzulu. The program ran until 2022.

Glimpses of two MSF teen club sessions at Namibambo Health Center in Chiradzulu district. Malawi 2022 © Francesco Segoni/MSF

Successes and the path ahead

After over 20 years of collaboration with MSF, Chiradzulu district health authorities and their partners have fully taken over all patients and activities between over the last two years, ensuring the continuity of HIV treatment and care. The Chiradzulu project counts among its successes:

- Reaching 55,000 people living with HIV in Malawi from its launch to its closure this year;

- Making HIV care more accessible by decentralizing care, especially through mobile clinics;

- Increasing health care staff capacity by delegating some tasks to less specialized health care staff;

- Reinforcing the importance of counseling in HIV care, particularly for young people;

- Setting a benchmark for HIV care in Malawi;

- Influencing global WHO guidelines through MSF research and advocacy;

- Meeting the UNAIDS “90-90-90” target in Chiradzulu district and improving nationwide numbers. Out of 990,000 people living with HIV in Malawi today, 93 percent know their status, 91 percent are on ART, and 85 percent have suppressed viral loads.

While the number of HIV-positive people in Malawi remains high, this is due to the number of people who have survived and are living with HIV. Having achieved these successes, Malawi’s Ministry of Health has the capacity to take over from here.

These numbers are monumental, but they do not mean that the struggle against HIV is over. Malawi still has one of the highest HIV prevalence rates in the world, with 990,000 HIV-positive people out of a population of nearly 20 million. All over the world, there are people living with HIV who continue to face stigma and barriers to accessing care. Cutting critical funding to PEPFAR—the US government initiative to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic—at this time would undercut decades of progress made with projects like MSF’s in Chiradzulu. These initiatives save lives and their support remains vital.

“In 2001, when the counselor said ART could prolong my life, I thought it would be two to three years,” recalls Fred, who is now 63. “But here I am, 22 years later.”