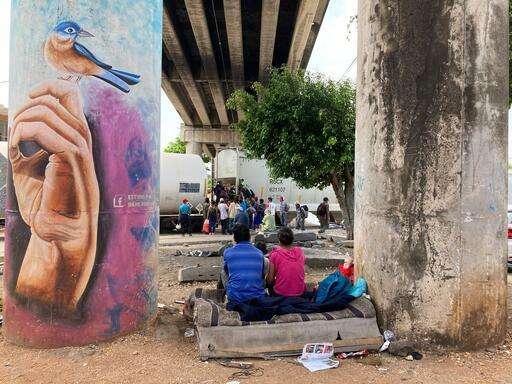

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams have witnessed the effects of increasingly harsh migration policies enacted by the United States, Honduras, Mexico, and Guatemala.

Migrants and asylum seekers fleeing violence in their countries of origin face repeated raids and arbitrary detentions on the southern border of Mexico, in addition to the Title 42 order, which has been misused to authorize mass expulsions ostensibly for public health reasons related to the COVID-19 pandemic, effectively blocking the right to seek asylum in the US.

These measures are making the treacherous journey undertaken by migrants and asylum seekers even more dangerous. In these testimonies, men and women on the move in Mexico describe their experiences.

“Now I know that I cannot protect my children”

Maria, 33, is from Guatemala.

We had to flee Guatemala because my husband handled confidential information in his job and the gangs asked him for it. They were threatening him. They detained him and beat him. They went to my house and tried to take my daughter from me. My son was detained by a man who told him that his father had to cooperate.

They told us they were going to kill my children. We decided to leave the country for our children's sake. The four of us left together and we traveled across Mexico. We faced difficulties; we slept on the floor—very difficult situations, but we came with the idea that if we could put up with it all we would be better off.

We walked to the southern border of Mexico and there we took a bus to Mexico City. The next day we took buses to Monterrey and Reynosa, where immigration agents grabbed my husband and my son. My daughter and I were not detained so I continued, and my husband ended up in a shelter in Monterrey. I continued, because what was I going to do with my daughter? Three days later, I crossed the river into the United States.

It was very difficult to get on those rafts at night, without any light. We walked in the hills, and at the river we got on a raft and got off on the other side, in the US. On the shore we walked along a path. We were stopped by patrols.

They shone flashlights at us. They began to choose people, and depending on the age of the children, they separated us. My daughter is four years old, [so she stayed with me]. They put us on a bus and after an hour they gave us water and some biscuits. The children were seen by a doctor, they took fingerprints, photos, and then they put us in a large tent with some little rooms with mats. As they were going to give me a mat they said no, that I had to wait.

A policewoman arrived with a file with my photo. She said that they were going to move us to another center where they would process me more quickly because they were overloaded there. Another bus. They took us to a place [that was] like a small police station with a cell. There they put all the women in with the children. We slept on the floor.

They gave the children juice, but they didn't eat because they gave them some trays of vegetables that smelled bad. I gave my daughter a taste and she started vomiting. I didn't give her anymore because if she kept vomiting she was going to become dehydrated. No more than one change of clothes is allowed. They take away clothes that aren’t allowed and throw them away. They also take the children’s clothing, even if it is cold.

They put us on a bus around three in the morning. That was concerning because we were saying, “We have not been processed, they never asked us anything or took a statement from us, nor did they ask us where we were going in the United States.” Then I realized it: from the bus I saw the river again and an officer with a black shirt and a Mexican flag.

We approached him and he asked us, “What are you doing here? Why are they sending me Hondurans?” I told him that I am from Guatemala and he replied, “It does not matter, you are not Mexican and I do not know why they are sending you.” Then another woman started crying and he told her, “The United States does not want you, if they are sending you back it is because they don't want you there.”

They took us to the migration center. I told them that I didn't know what I was going to do, I didn't have anything—no money, no phone. I had entered the US through the Reynosa border and they returned me to the Nuevo Laredo border [about 160 miles away]. I had no way of communicating with anyone. There were about 20 mothers with our children. Two buses arrived to take us to a shelter. Many of us agreed to go because we had children of different ages, some were carrying babies.

In the municipal shelter we received help. I was able to communicate with my family. My husband told me that he was in pain, that he had seen a doctor and that he needed surgery. We do not have the resources to pay for surgery. He is looking after my son and if something happens to him, my son will be left alone in the shelter.

You believe that story that they tell you—that the trip is going to be three days and that the United States immigration [system] will welcome you and it is not true. You come with the idea of a future to keep your children safe and find work. We thought that the president of the United States had said 100 days. What we did not understand is that it was 100 days in which he was not going to deport people. We were under the impression that in those 100 days we would be able to enter the country, but it is not like that. And many people are sending their children alone, when I crossed the river there were many children who were alone.

In the migration centers there were portable toilets, wash basins, and soap, but they did not assess the mothers. At no time did a doctor check us, they did not take our temperature, they did not give us face masks. They did not ask us to distance ourselves in cells that were overcrowded. In each cell there were 50 women with children. We're talking about more than 100 people per space, with mats on the floor, one next to the other. Here in Mexico, doctors came to see us, but only to see us—to measure our height and weight, what blood type we were. They did not evaluate us, or do a real medical check-up.

My husband is in a shelter in Guadalupe, Nuevo León. Right now what we are waiting for is to return to our country so that he can be treated, because here we do not have access to anything. We are illegal people, so we do not have any help. I am afraid to return to Guatemala. I know what happened to us will continue to happen. We are going to go back and hope that somehow our situation will be resolved, at least so my children are safe, because here I really do not feel safe either.

I feel like I failed, because everything we had to go through on the way was difficult. But I thought it was going to be temporary and that I was going to protect my children. Now I know that I cannot protect them. I couldn't protect them here either, and if the United States does not even give us the opportunity to present our case, then the most likely thing is that I will return to my country. And I feel like it's going to be like swimming against the current.

Many women come with the idea that since their husbands are in the US they will be reunited with their family. Others come to look for work. Others like us are fleeing so they won't kill us, but even that does not matter, because they do not listen. There is no opportunity for you to present your case. Even if you have evidence, you don't get a chance. It does not matter, there is no way across, they say that the borders are closed.

The immigration agents treat you badly. You ask a question and they yell at you, they push you. To search the minors, they put them all up against the bus with their hands up and pushed them. I thought about my son and I did not want to think that my son would be beaten because I saw how they pushed them around to search them.

We as migrants . . . are fleeing and we have no intention of harming anyone. But I don't think everyone understands that.

"I don’t sleep because while my son sleeps I keep watch"

Kimberly, 29, is from Copán Ruinas, Honduras.

I am 29 years old, I used to work in the fields. I have three children who are 15, 11, and 8 years old. I am traveling with my 11-year-old son, a fellow parishioner, and his baby. My other children stayed with my mother in Honduras.

With the hurricanes in Honduras, I lost my house—I lost everything. I ended up on the street. My goal is to get to New York, where my brother is. It's been 20 days since I entered Mexico. We have slept in the hills, in the street, endured hunger and sleepless nights because we have no money. We could only find a shelter in Salto de Agua [in Chiapas state, Mexico]. We stayed there for two nights and from there we have just been walking and sleeping wherever we are when night falls.

The shelter here, [Casa del Migrante Diócesis de Coatzacoalcos] is closed. They have given us food and coffee, but we can no longer sleep inside. Yesterday I begged them to let me wash with my son because the truth was that we hadn't been able to for two days and they only let me in to wash with the two children, my parishioner's baby, and my child, and then they took me out.

We eat thanks to the goodwill of the people.

[Mexican authorities] took from us the little money that we brought from Guatemala. At all the checkpoints they asked for 150 or 200 quetzals [about $20 or $25] and threatened to deport us because they asked for my authorization and passport. I have neither.

I am afraid of staying on the street because anything can happen to us. I am afraid that my son will be taken from me. I have not been able to sleep. I don't sleep because while my son sleeps, I keep watch.

I am also afraid of being deported to my country. The situation is very hard. If I had a job there, I would not risk my son, nor would I have left my other children there.

We go around asking for water, we fill the bottles and some people give us money to buy food. We always use masks, and gel, and I try to keep my distance from people.

My son is very tense and he says, "Mommy, why don't we move on?" But I have to wait until the train leaves. One departed just now, but I didn't want to get on because there were a lot of people and I would rather wait for another ten trains so my son can travel safely.

I feel sad about risking my son on this journey, and not being able to give him the comforts that other children have. What worries me most is his safety and not having money to give him food. It's what hurts me the most.

His health has deteriorated a bit. Because sometimes they give me food, I tell him "Eat everything, my love." And he says, "If you don't eat, I don't eat." And then I tell him "I'm not hungry." Even if I am, I tell him that so he can eat, but if I don't eat, he says he's not hungry either.

I say that if God gives me the opportunity to get there, my future will be different because my dream is to rebuild a home for my children and prepare them for life with studies, both for him and those I left in Honduras. To have a good job, no matter what it is, and help my family. To get there so my son has a place to sleep and to be able to rest in a safe place.