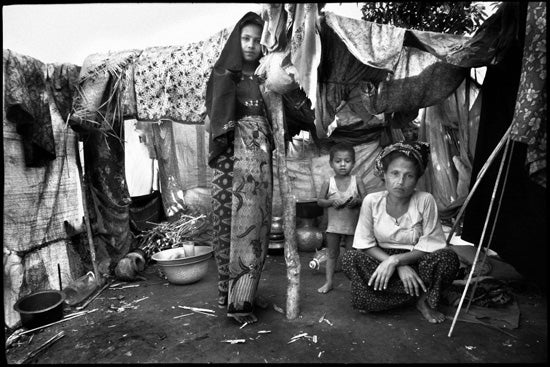

Bangladesh 2007 © Eddy van Wessel

A Rohingya family gathers together in Tal camp, a makeshift camp in Bangladesh where thousands of the Muslim minority population from Myanmar are living in terrible conditions.

Weak, dehydrated, and traumatized, the Rohingya people from western Myanmar, who arrive on Thailand’s shores after crossing the Andaman Sea, come with alarming stories.

The Rohingya, a minority Muslim ethnic group, have suffered decades of restriction and indignity in Myanmar, which has led countless people to flee to neighboring Bangladesh, to Thailand, and beyond. Those who make the often risky and dangerous journeys find their suffering far from over. They face detention, deportation, or life in overcrowded and unsanitary refugee camps. From its projects in Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Thailand, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has witnessed first-hand the medical consequences of the Rohingya’s chronic humanitarian crisis.

“I was relieved to make it to shore alive,” said one man who came by boat to Thailand last year. “At sea, I saw another boat carrying around 80 people sink in front of my eyes. I think everyone died.”

MSF has been granted access to groups of Rohingya detained by the Thai authorities on a number of occasions during recent years. “On arrival, their medical condition speaks volumes about the experience that they have undergone at sea,” said MSF head of mission in Thailand, Richard Veerman. “We generally treat people for dehydration, skin disease, and bruising, which vary in severity, depending on the length of their journey. Last year, we found out that one immigration detention center was holding 600 Rohingya; many had been detained for around three months and were showing signs of stress. Some appeared to be suffering from severe psychological trauma."

Over the past two years, the number of Rohingya arriving in Thailand has reached an all-time high. “This is a clear indication that more needs to be done, not only to ensure adequate assistance on the spot, but to address the root cause of the problem back in Myanmar,” said Veerman.

Bangladesh 2007 © Eddy van Wessel

A Rohingya woman gets medical care for her child inside Tal camp.

"I don't believe I'll ever go back. It is evident that things are still very bad in Myanmar and even if we live with minimum support and help in Bangladesh, at least we don't have to fear,” said another Rohingya man living in Tal camp.

Cox’s Bazaar, on the eastern shores of Bangladesh has seen countless Rohingya come and go over the years—those who have fled from Myanmar and those who pile into overcrowded boats headed for Thailand and further abroad. For those who stay, living can be extremely tough. MSF began providing health services for the Rohingya in Bangladesh in 1998, most recently assisting about 7,500 people who struggled to survive, otherwise unaided, in atrocious living conditions in Tal camp. “The overcrowded, unhygienic living conditions were a breeding ground for respiratory tract infections and skin diseases. Diarrhea was rife and many of the children were malnourished. Mental health problems added to the burden, and an MSF program was started to support those struggling with the psychological impact of life in the camp,” said MSF medical coordinator in Bangladesh, Gabi Popescu.

"People fear that they will be punished for marrying without permission, for having children without permission, for travelling without permission, for having left without permission..."

“Over the years I have heard many reasons why people fled from Myanmar. A woman and her three children left following her husband’s arrest, in fear for her family. Another couple left, the woman some months pregnant, out of fear of the repercussions they would face for being unable to afford the official marriage license, not to mention the child birth license,” said Popescu. The Rohingya living in Northern Rakhine State are legally obliged to purchase expensive marriage permits, unlike the rest of the population. Children being born out of marriage often results in high informal fines or imprisonment and a two-child limit applies.

“My daughter was pregnant and took the root drink and was given a rough abdominal massage from a relative to kill the baby. When we went to see the doctor she was having fits and bleeding badly. I was scared the authorities would force us to pay a big fine or arrest her because she was pregnant and not married. We didn’t take her to the hospital as the doctor told us to but we went to the local healer. She died the next day,’’ said a woman in Tal camp.

Despite the daily hardships people face in Bangladesh, returning to Myanmar is an option few Rohingya seem willing to consider. “People fear that they will be punished for marrying without permission, for having children without permission, for travelling without permission, for having left without permission, for doing anything without permission, and permission costs money, something that the Rohingya have little of—partly due to numerous other discriminatory measures imposed upon them,” said Popescu.

MSF has worked for 16 years in Rakhine State, where the Muslim population’s health status is fragile. An estimated one million Muslims—known as Rohingya only outside of Myanmar—live here, and the fact that they require authorization for so many things, including travel outside their villages, affects their access to healthcare—especially in emergencies—and increases their vulnerability. In 2007, during MSF’s last major nutrition intervention, 90 percent of the malnourished children treated were Rakhine Muslim, even though they constitute only 45 percent of the population in the affected area.

“Without a fundamental solution for the Rohingya, not only in countries where they seek asylum but at their origin, there is no apparent end to this humanitarian crisis,” said MSF general director Hans Van De Weerd.