MSF is providing care, including mental health care, to patients in Pakistan's Lower Dir province, where the security situation remains volatile.

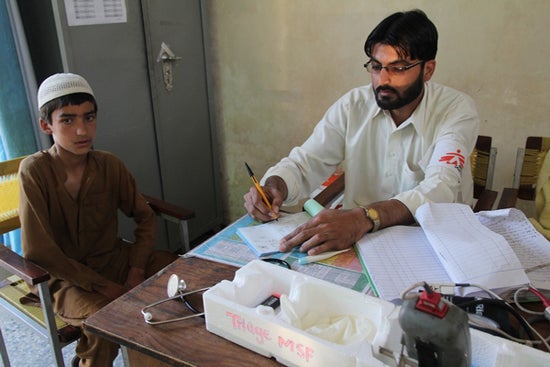

Pakistan 2012 © P.K. Lee/MSF

An MSF staff member and a young patient in the triage area of the DHQ hospital in Timergara

“I still remember there was a big bomb blast in April 2010, about 300 meters [about 984 feet] away from our hospital. Within a few minutes, dozens of injured patients were already outside the emergency room. We needed to quickly identify who needed to be attended first,” recalls Dr. Muhammad Zaher, who is working with Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) as assistant medical focal person in Timergara, in the Lower Dir district of northwestern Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) province.

Until a few years ago, Lower Dir, on the border with Afghanistan and the tribal areas of Pakistan, was the scene of fighting between the military and armed opposition groups. The security situation in the area remains volatile, and bomb blasts, clashes, and targeted killings still take place today.

Traffic accidents are another major cause of serious injury in this rugged and hilly region. “The roads are very bad,” explains Dr. Zaher. “Each small passenger van here usually carries up to 25 or even 30 people. When there is a car crash, it can easily cause many injuries.”

MSF has been supporting the District Headquarter (DHQ) hospital in Timergara since 2009. The team has implemented a new routine triage system in the emergency department, and has also developed a plan to deal with the arrival of many people in need of emergency care.

Handling such incidents is a race against time. The mass casualty plan allows medical staff to rapidly identify and prioritize patients’ medical needs based on a few vital signs. Patients are then categorized: “green” means the patient is stable and can wait for few hours; “yellow” means he or she can wait for an hour; “red” means lifesaving treatment is required within one minute; and “black” means deceased or beyond help. “Red” patients are immediately sent to the resuscitation room. “This allows us to provide good quality medical care to a maximum number of patients, and save a maximum of lives within a minimum of time,” says Dr. Zaher.

A routine triage system, using the South African Triage Score (SATS), has also been implemented to improve day-to-day patient care in the emergency department. Upon arrival, every patient receives an initial screening, in which staff measure blood pressure, heart rate, and clinical conditions to help prioritize patients’ medical needs. In the first three months of 2012, a total of 12,162 patients passed through the triage system, and 3,271 patients were treated in the resuscitation room.

Patient Story: Ali*

Ali, a five-year-old boy, fell five meters [about 16 feet] from the roof of a house while playing with other children. “He was unconscious,” says Ali’s neighbor. “Since there were no other male adults in his home, his mother sought help from me. So I immediately drove him to the hospital.”

At the emergency department of the DHQ hospital in Timergara, Ali was immediately sent to triage, and was then taken to the resuscitation room. There he received initial treatment and underwent a more detailed check-up. “The CT [computer tomography] scan showed he had fracture on the right side of the skull,” explains Dr. Thomas Pols, an MSF emergency doctor. “Luckily there was no bleeding inside. He needs to stay in the observation room for at least five to six hours. If he has nausea or vomiting, or his level of consciousness declines, we will refer him for further treatment. We see this kind of trauma case about two to three times a day. Children falling from roofs is very common here. And some of them have very extensive injuries that are not treatable. This is one of the public health problems here, for which more effort on prevention or safety education is needed.”

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his anonymity.

There is a serious lack of good-quality specialized health care in Lower Dir, and MSF also provides emergency surgery in Timergara for patients from all over the district. Most patients in a serious condition are referred to the DHQ hospital, while some are sent as far as neighboring districts, such as Upper Dir and Bajaur Agency.

“I got shot by my business partner. I was in a hilly area bordering with Afghanistan. The road was rough. I was put on a bed carried by people for an hour and then was sent to nearest Samar Bagh Tehsil hospital by car for another hour. Having given me IV [intravenous] fluids, they referred me here,” says Anwar [patient’s name changed to protect anonymity], who had emergency surgery in Timergara’s DHQ hospital to remove the bullet and shrapnel in his groin and is now receiving post-operative care.

“We borrowed 5,000 PKR [about $54] from the doctor in Samar Bagh hospital. We thought we would need to pay for the surgery here. We are glad that it’s free of charge. Otherwise, even if we sold our house and all the cattle, we would still not have enough money to pay for it,” says Anwar’s uncle.

MSF currently supports the emergency department, emergency surgery, and the mother-and-child department in the DHQ hospital in Timergara. Mental health care is also provided to patients in these departments. All medical care provided by MSF is free of charge.

Introducing a New Concept: Mental Health Support in Northwestern Pakistan

Mental health services are scarce in Pakistan, and Lower Dir is no exception. There are very few psychologists for the district’s estimated population of 1.2 million people. Indeed, the MSF team in Lower Dir knows of only one.

The volatile security situation in Lower Dir is affecting many people. Some have difficulty coping with the psychosocial consequences of violence. There are people suffering from post-traumatic stress, while others face chronic everyday stress for which their usual coping mechanisms are no longer sufficient.

In the emergency department at Timergara DHQ hospital, MSF staff has seen patients whose medical problems are in fact related to mental health issues. A number of people come in after attempting suicide, and many are emotionally agitated or in a depressive condition. In response to this situation, MSF started providing mental health counseling and psychosocial support in the hospital in February 2012.

The mental health team is made up of both male and female staff. They provide individual and group counseling to patients referred from the mother-and-child health department, the emergency department, and the post-operative wards.

Saida is one of two female counselors. “Every day I see an average of seven patients,” she explains. “The common cases in the women’s post-operative wards are patients who have lost a baby; had stillbirths or hysterectomies; or who are suffering from post-partum depression. For cases from the emergency room, it’s more related to domestic issues, socio-economic problems, or even suicide attempts.”

“Most of the attempted suicide patients that we have seen are women,” Saida adds. “People find their emotional and financial support within the families, but when there is a conflict, it can be very distressing for everybody. They don’t know how to find ways to handle it.”

For most of the people in Lower Dir, mental health is a totally new concept. “People have no idea about mental health,” says Saida. “They think all body pains and other symptoms are due to physical problems. They do not make the link between distressing events and body pains. They ask for medicines instead of counseling. We explain that this is actually due to the stress and we can talk about it.”

In order to increase general awareness of mental health issues, the team offers psychosocial support to caretakers as well as patients. “Now we have patients coming to us by themselves, as they are getting more aware about mental health issues and the availability of the service,” says Saida. “There are also female patients who are becoming more willing to come back for follow-up counseling. They want to share their feelings and look for help to solve their problems.”

At the end of May, MSF had conducted 444 individual mental health sessions and 30 group psychosocial sessions.

MSF has been working in Pakistan since 1986. Apart from Timergara, MSF is working in Dargai, Hangu, and Peshawar in KPK province. MSF also has projects in Quetta, Kuchlak, Dera Murad Jamali, and Chaman in Balochistan province; as well as Kurram Agency in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. A project in Karachi, Sindh province, is going to open later this year.

For all its activities in Pakistan, MSF relies solely on private donations from individuals around the world and does not accept funding from any government, donor agency, or from any military or politically-affiliated groups.