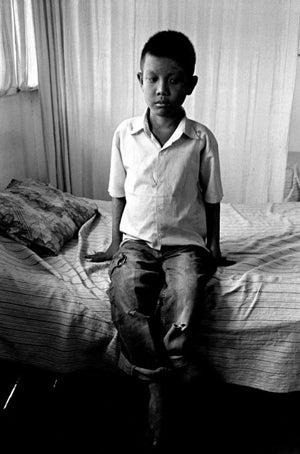

Zimbabwe 2006 © Michael G.Nielsen

An MSF Doctor examines a young HIV-positive patient.

There are an estimated 2.1 million children living with HIV/AIDS,1 90% of whom are from sub-Saharan Africa. Only 10% receive any treatment for the disease.2

The vast majority of these children become infected with HIV through transmission from the mother during pregnancy, childbirth or breastfeeding. It is therefore imperative to continue to work towards the prevention of this transmission, something that has almost been fully achieved in industrialized countries.

But recognizing the importance of prevention programs must not mean ignoring the treatment needs of the more than two million children currently living with HIV/AIDS. In Sub-Saharan Africa, without treatment, a third of the children with HIV will have died before their first birthday, and a half of them will die before their second birthday.

Children left behind

Kenya 2007 © Matthias Steinbach

In wealthy countries, successful measures to prevent mother-to-child transmission mean that only a small number of children are infected with HIV. Pediatric HIV/AIDS is therefore largely a problem in poor countries only – this is a major factor explaining why diagnostics and treatments for children lag behind. As there is little financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies to develop products specifically to treat children, it has taken much longer for pediatric versions of antiretroviral drugs to be made available than adult formulations. Even when pediatric versions do exist they are considerably more expensive than the drugs designed for adults.

MSF’s experience with pediatric HIV

MSF started providing antiretroviral therapy to children in December 2000. Over the last five years, nearly 10,000 children under the age of 15 have started antiretroviral therapy in our programs worldwide, of which 4,000 are children under five years of age. Our experience has shown that children respond very well to treatment and can improve quickly. MSF’s largest pediatric project in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe has been very successful in reducing the mortality rates amongst the 1,800 children on antiretroviral therapy there.3

What needs to be done to scale up treatment?

There are nevertheless practical issues that currently make diagnosing and treating children much more difficult than adults. These need to be addressed.

Scale up early infant diagnosis

Kenya 2007 © Matthias Steinbach

Detection of HIV infection in infants is crucial so that antiretroviral therapy can be started as quickly as possible. The new WHO recommendatdion is for all children less than 12 months of age who are known to be HIV positive regardless of immune status. However, it is currently very difficult to test HIV in children under 18 months due to the persistence of maternal antibodies that are present for the first 18 months of the child’s life. Currently, the only way to test children under 18 months is to use a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) machine, which is a complex DNA-based diagnostic tool.

The PCR machine is expensive, requires trained personnel and advanced laboratory infrastructures – all factors that make it difficult for national programs to use. Additionally the machines often only exist at the centralized laboratory level which means that tests carried out in rural areas need to be sent to a central structure, and the results sent back again, a process which can take between one to three months, during which time there is the risk of losing the patient to follow up. What is needed is a test that allows the mother to be informed about her baby’s HIV status within a day.

But until a more practical long term solution is found, relying on PCR remains the only option for diagnosing children under 18 months, and as such, every effort should be made by donors and implementers to ensure that it is available and used.

Treatment – painfully slow progress

© MSF

A 9 year old HIV patient, who lost both his parents to AIDS. His health has improved significantly since having started ART.

Today there remains, despite some progress, a wide gap between the range of treatment options available for adults and those for children. Of the 22 drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for adults, eight are not approved for use in children, and nine do not exist in pediatric formulations.

Drug companies were very slow to design treatments specifically formulated for children. The first pediatric fixed-dose combination (an FDC simplifies treatment by combining several drugs in one pill) to be approved by the World Health Organization (WHO), appeared six years after the adult ones. Currently it is the only pediatric FDC that has been quality assured by WHO - compared with 42 for adults.

Many more drugs for children could potentially exist but it is taking a painfully long time for these drugs to be studied for use on children. This process needs to be accelerated – at the moment there are simply not enough treatment options for children. If a child should develop resistance to a class of antiretrovirals there are not enough alternative medicines available, even though these drugs exist for adults.

Additionally, what is urgently needed is a good treatment for young children co-infected with tuberculosis (TB), one of the most common and serious opportunistic infections in HIV. For example, efavirenz – an antiretroviral that has been registered in the U.S. since 1998 – still has no safety or efficacy data for its use in children under three. Efavirenz is particularly needed for children with HIV/AIDS who are co-infected with TB because it does not interact significantly with TB drugs. However, until the drug is tested on children we are not able to use it.

Not adapted to real life conditions

Kenya 2007 © Juan Carlos Tomasi

Of the limited number of antiretrovirals to treat HIV that do exist for children, many of them are ill-adapted to the context where the majority of HIV infected children live. Some of them are syrups that come with logistical constraints as they are heavy or require refrigeration, others are powders that need to be mixed with clean water, all factors that make them harder to use in remote settings. Other formulations have an unpleasant taste or a high alcohol content making it harder to dispense to children. When producing pediatric drugs more thought needs to be given to where those drugs will be used, and by whom.

Ensuring that children with HIV/AIDS are no longer neglected requires:

- Boosting diagnosis: more effort and funds to be placed on diagnosing children under 18 months so that treatment can be started as soon as possible

- Improving treatment: governments and other actors to start treating more pediatric HIV patients

- Accelerating drug studies for pediatric treatments: children need more treatment options to be available sooner

- Putting the constraints that exist in remote settings at the centre of the development of pediatric HIV formulations

- UNAIDS 2008

- WHO, Towards Universal Access, scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector, Progress Report 2008, p. 95

- Parreño F, Nyathy M, Palma PP, Roddy P, Alonso E. Analysis of clinical and immunological outcomes of an HIV positive paediatric cohort treated at Mpilo Hospital in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe [abstract]. IAC 2008, Mexico City. LBPE1155