MSF is adopting new strategies to fight drug-resistant tuberculosis among children and families in Tajikistan.

Tajikistan 2012 © Natasha Sergeeva/MSF

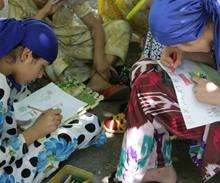

Young MDR-TB patients take part in developmental activities at the pediatric hospital in Dushanbe.

For the first time, children in Tajikistan with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) are receiving treatment for the life-threatening disease. Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has opened a new ward in Machiton hospital, near Tajikistan's capital of Dushanbe, where it plans to treat 60 to 100 children with TB, plus their family members, over the next three months.

“We call our program ‘family TB’,” says MSF Medical Coordinator Nana Zarkua. “It’s not uncommon in Tajikistan for several members of one extended family to be sick, and what makes our program special is the family approach to the problem.”

“For MSF, a child often serves as an entry point into a family with TB,” says Zarkua. “When we identify a sick child, we can provide the family with information on how to reduce the spread of the disease, and we can trace contacts within the family to see who else might be infected.”

Systematic Neglect

In Tajikistan—one of the poorest countries of the former Soviet bloc, with the highest rate of TB in Asia—poverty and an underfunded health system have led to the systematic neglect of people with drug-resistant forms of the disease. TB is highly contagious, and undiagnosed and untreated the disease spreads quickly among friends and relatives, destroying families and creating stigma and fear.

Children are the most neglected of all. Until MSF launched its new program, not a single child in Tajikistan had received treatment for MDR-TB. “The common belief among the local TB doctors,” says Zarkua, “is that children shouldn’t be treated with second-line drugs; others even deny the possibility of drug-resistant TB in children, because it is so difficult to diagnose and prove.”

MSF doctors hope to find a way to rapidly diagnose DR-TB amongst this age-group, and—until pediatric formulations of TB drugs are available—will treat young patients using adult drugs, a strategy that has proved successful in MSF programs elsewhere in the world. MSF is also renovating an abandoned chalet on the hospital grounds to use as a sputum induction room, where staff can use the procedure to acquire sputum samples suitable for TB testing from children who often don't spontaneously produce enough sputum to test. When complete, this facility will be the first of its kind in Central Asia.

Games and Creativity

Previously all child TB patients in Tajikistan had to stay in hospital for the duration of their treatment, isolated from their families and with few distractions or amusements. But in Machiton hospital, children are treated on an outpatient basis whenever possible, so that they can stay with their families and continue with normal life.

Children in the hospital are encouraged to take part in "development activities"—playing games, reading, drawing, and doing puzzles with dedicated MSF staff. “Our psychosocial team has strategies for every age group, so that the kids receive the stimulation that will help them develop in line with their age,” says Zarkua.

Back to School

When patients are no longer contagious, MSF staff will help persuade their schools to let them continue their education. “We have already had one particularly successful example, when MSF pushed for a smear-negative teenage girl to be accepted back at school,” says Zarkua.

At the hospital, nutritious food is provided, and families of children receiving outpatient care will receive weekly parcels containing high-protein foods—meat, fish, or condensed milk—that they might not otherwise be able to afford. Mobile phones and money for transport provided by MSF will help ease families’ communication and travel difficulties as well.