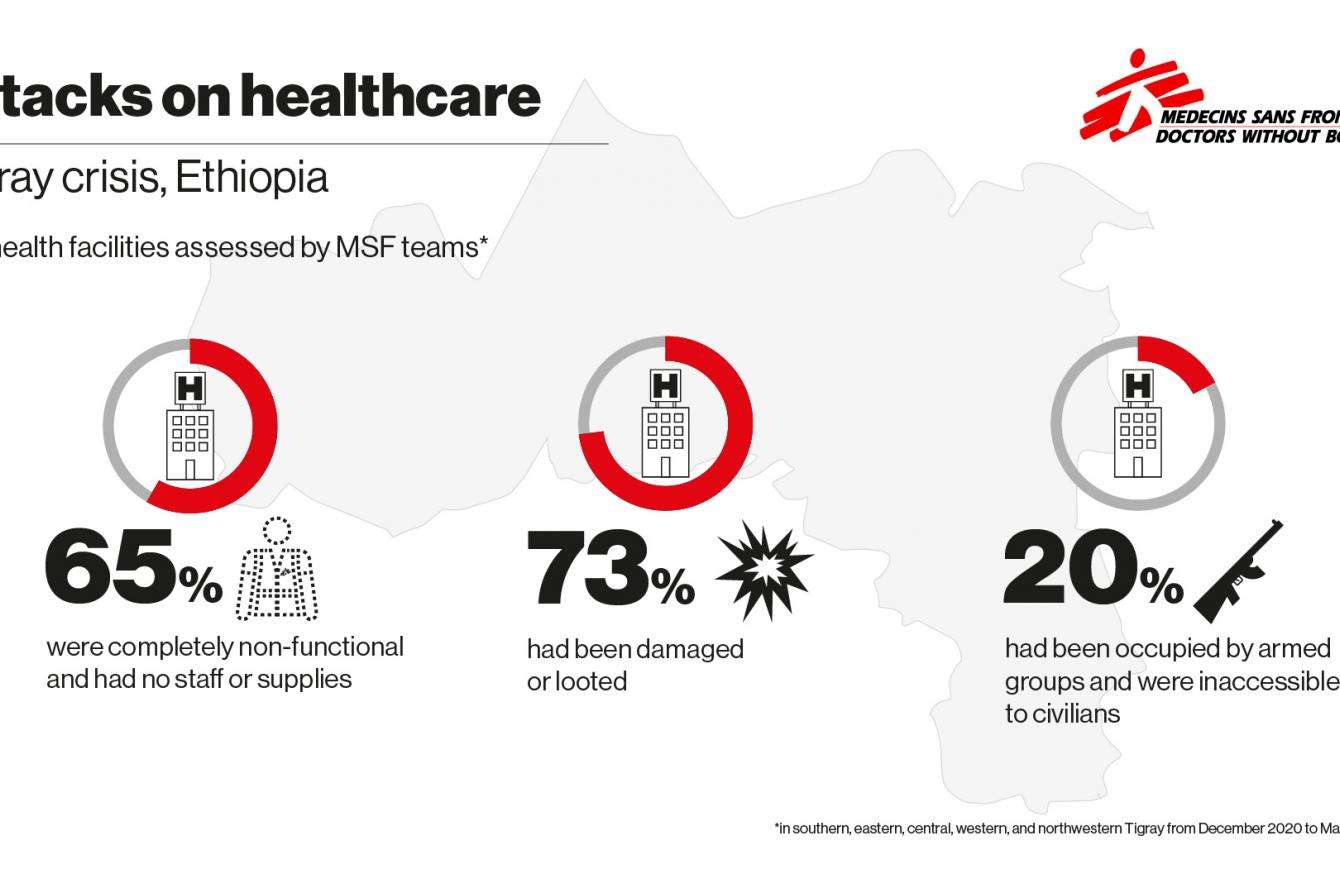

ADDIS ABABA/NEW YORK, March 15, 2021—Health facilities across Ethiopia's Tigray region have been looted, vandalized, and destroyed in a deliberate and widespread attack on health care, the international medical humanitarian organization Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) said today, sharing the findings of an assessment by MSF teams.

Of 106 health facilities visited by MSF teams in Tigray from mid-December to early March, nearly 70 percent had been looted and more than 30 percent had been damaged. Only 13 percent were functioning normally.

"The attacks on Tigray's health facilities are having a devastating impact on the population," said Oliver Behn, MSF general director. "Health facilities and health staff need to be protected during a conflict, in accordance with international humanitarian law. This is clearly not happening in Tigray."

The looting of health facilities continues, according to MSF teams. While some looting may have been opportunistic, health facilities in most areas appear to have been deliberately vandalized to render them nonfunctional. In many health centers, such as in Debre Abay and May Kuhli in northwestern Tigray, teams found destroyed equipment, smashed doors and windows, and medicine and patient files scattered across floors.

In Adwa hospital in central Tigray, medical equipment, including ultrasound machines and monitors, had been deliberately smashed. In the same region, the health facility in Semema was reportedly looted twice by soldiers before being set on fire, while the health center in Sebeya was hit by rockets, destroying the delivery room.

Hospitals occupied by soldiers

One-fifth of the health facilities visited by MSF teams were occupied by soldiers. In some instances this was temporary; in others, the armed occupation continues. In Mugulat, in eastern Tigray, Eritrean soldiers are still using the health facility as their base. The hospital in Abiy Addi in central Tigray, which serves a population of half a million people, was occupied by Ethiopian forces until early March.

"The army used Abiy Addi hospital as a military base and to stabilize their injured soldiers," said MSF emergency coordinator Kate Nolan. "During that time it was not accessible to the general population. They had to go the town's health center, which was not equipped to provide secondary medical care—they can't do blood transfusions, for example, or treat gunshot wounds."

Ambulances seized

Few health facilities in Tigray now have ambulances, as most have been seized by armed groups. In and around the city of Adigrat in eastern Tigray, for example, some 20 ambulances were taken from the hospital and nearby health centers. Later, MSF teams saw some of these vehicles being used by soldiers near the Eritrean border to transport goods. As a result, the referral system in Tigray for transporting sick patients is almost nonexistent. Patients travel long distances, sometimes walking for days, to reach essential health services.

Many health facilities have few—or no—remaining staff. Some have fled in fear; others no longer come to work because they have not been paid in months.

Devastating impact on the population

Before the conflict began in November 2020, Tigray had one of the best health systems in Ethiopia, with health posts in villages, health centers and hospitals in towns, and a functioning referral system with ambulances transporting sick patients to hospitals. This health system has almost completely collapsed.

MSF staff conducting mobile clinics in rural areas of Tigray hear of women who have died in childbirth because they were unable to get to a hospital due to the lack of ambulances, rampant insecurity on the roads and a nighttime curfew. Meanwhile many women are giving birth in unhygienic conditions in informal displacement camps.

In the past four months, few pregnant women have received antenatal or postnatal care, and children have gone unvaccinated, raising the risk of future outbreaks of infectious diseases. Patients with chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension and HIV, as well as psychiatric patients, are going without lifesaving drugs. Survivors of sexual violence are often unable to receive medical and psychological care.

"The health system needs to be restored as soon as possible," Behn said. "Health facilities need to be rehabilitated and receive more supplies and ambulances, and staff need to receive salaries and the opportunity to work in a safe environment. Most importantly, all armed groups in this conflict need to respect and protect health facilities and medical staff."

MSF teams are rehabilitating a number of health facilities across the region and providing them with drugs and other medical supplies, as well as providing hands-on medical support in emergency rooms, maternity wards and outpatient departments. MSF teams are also running mobile clinics in rural towns and villages where the health system is not functioning, and in informal sites where displaced people are staying. However, there are still rural areas in Tigray that neither MSF, nor any other organization, has been able to reach; MSF can only assume that people living in these areas are also without access to health care.