On Sunday, August 15, after months of intense fighting, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA, also known as the Taliban) entered the capital city of Kabul as the government collapsed. The IEA has declared that the war is over and assumed control over the country. Despite intense fighting in recent months, our teams did not stop providing vital medical care.

Christopher Stokes, senior humanitarian specialist, and Jonathan Whittall, director of the analysis department, have each spent years helping to coordinate lifesaving medical care with Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in Afghanistan. Here, they explain MSF's history of engaging with all parties to the conflict and how this approach enables our teams to deliver humanitarian assistance where it is needed most.

As United States forces withdraw from Afghanistan, putting an end to the longest war in US history, a new era has begun for a country that has seen invading forces come and go over the centuries. The news has been dominated by the Taliban forces swiftly taking control of the provincial capitals and seizing Kabul unopposed, as well as Afghans desperately trying to leave. We have seen Western embassies packing up, foreigners fleeing en masse, and many nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) ceasing to operate.

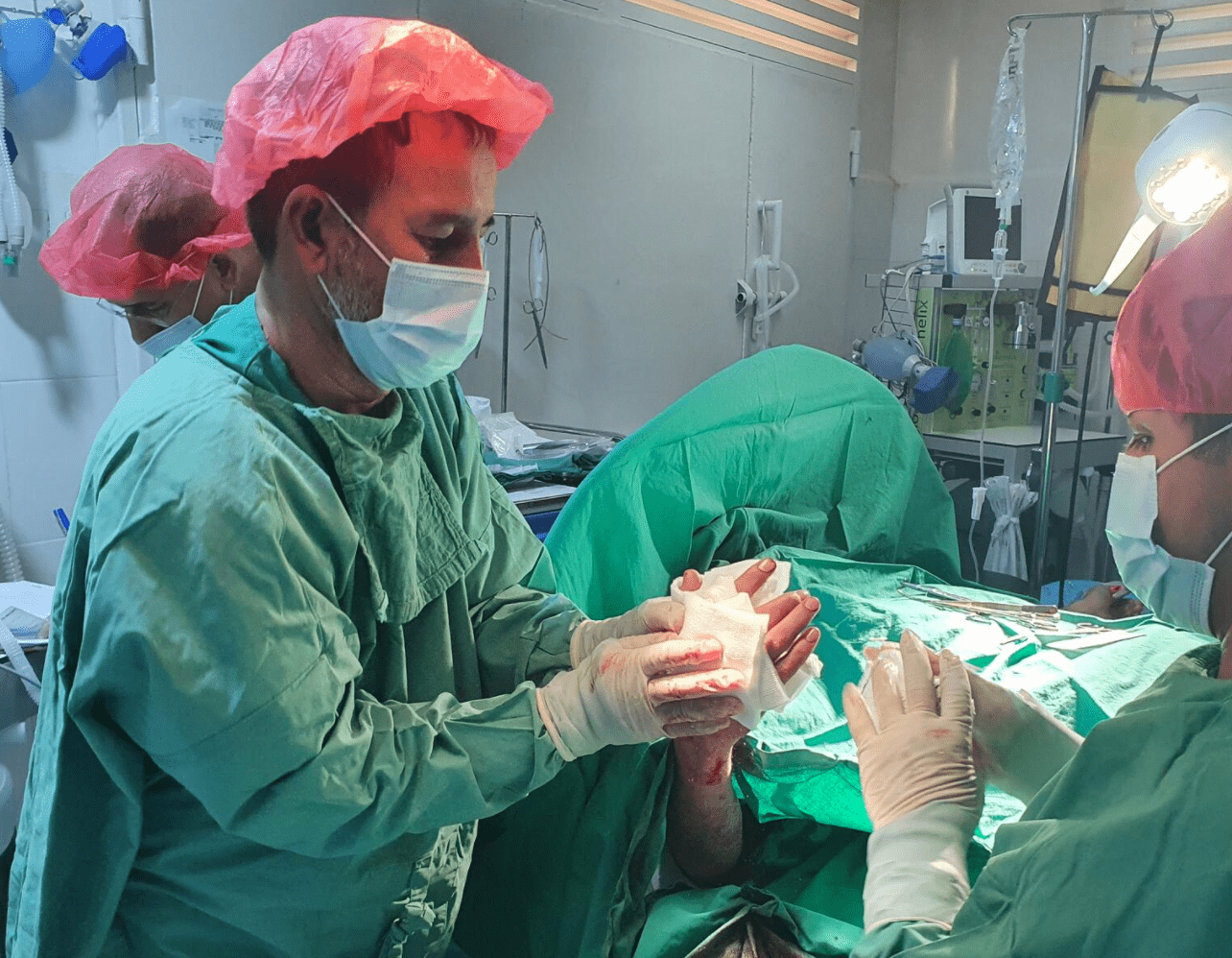

In contrast to these scenes, MSF and a handful of other humanitarian agencies have maintained their presence and activities at the height of the fighting, providing lifesaving assistance to the sick and wounded.

How is this possible? MSF has had successes and failures in Afghanistan, but the core of our approach has remained the same: we would only work if we had the explicit agreement of all parties to the conflict. That included the Taliban, the US forces, the Afghan National Army, and, in some cases, local militia groups.

Our principles of neutrality, independence, and impartiality, which can at times seem abstract, were operationalized by talking to all sides, refusing funding from governments, clearly identifying ourselves so as not to be confused with other groups that may have other interests, and by making our hospitals weapon-free zones. Whoever came to a privately funded MSF hospital had to literally leave their gun at the door.

When working in Kunduz or Lashkar Gah hospitals, we regularly explained to US, Afghan, and Taliban soldiers that we would never turn away any patient, be they a wounded government soldier, a car crash victim, or a wounded Taliban fighter. Our hospitals triaged based on needs alone. We worked according to medical ethics, not according to who was deemed a criminal, a terrorist, a soldier, or a politician. We often had to request US and Afghan soldiers to leave and return without their weapons if they wished to visit the hospital.

Our approach was often in contrast to the way in which the aid system—including humanitarian agencies—were being pushed by donors to build the Afghan state, to create stability in areas taken by Afghan forces, and contribute to the legitimacy of a fledgling US-backed government. Aid was the "soft power" to win over the population to the Afghan government, a key component of the hearts and minds strategy bolstering the "hard power" of military deployment.

Tellingly, when meeting a Western humanitarian donor in Kabul, they were unable to tell us where the humanitarian needs were the greatest but instead referred to a map of areas under the control of coalition forces (in green), under Taliban control (in red), and contested areas (in purple). They were sending aid to green and purple areas to help boost the military effort. International NGOs taking government funding from Western states involved in the fighting were shocked to see counterinsurgency language such as “clear and hold” creep into their funding grants. As one of the biggest government donors explained to us in Kabul: “The Taliban are making gains in this province. We told the aid agency to cover the province in wheat, and they did.”

But our approach did not always protect us. It was in 2015 that US special forces bombed our hospital in Kunduz after the province had been briefly taken over by the Taliban. It demonstrated to us the gray zones that exist in such conflicts: aid is tolerated and accepted when it boosts the legitimacy of the state, but it becomes susceptible to being destroyed when it falls into a territory where entire communities are designated as hostile enemies. This gray zone is cultivated by legal ambiguities between international and national law. [Editor's note: US airstrikes killed 42 people and destroyed the trauma hospital, which should have been protected under international humanitarian law. In April 2016, a US military spokesperson released the results of an investigation into the Kunduz bombing, concluding that “this tragic incident was caused by a combination of human errors, compounded by process and equipment failures.” No criminal charges were pursued.]

Following the destruction of our hospital, MSF engaged again with all parties to the conflict to clarify the respect for our medical activities. It was arguably our widespread public support and the political cost of the attack on MSF that ultimately served as our best safeguard against future so-called "mistakes" by US and Afghan forces. However, this form of deterrence through engagement and public pressure was of no use when our maternity hospital was brutally attacked in Kabul's Dasht-e-Barchi neighborhood, most likely by the Islamic State in Afghanistan, which has remained out of reach of our dialogue.

While MSF has been able to operate in provincial capitals, we have been unable to go into rural areas to address needs there. This has been one of the failures of MSF’s work over the past years. However, two weeks ago, when the Taliban entered the cities, we were able to continue working to treat patients: the sick and the wounded were able to receive care in facilities which we adapted to cope with the intensity of the fighting. In Helmand, Kandahar, Kunduz, Herat, and Khost our teams continued to work. Our health facilities today are full of patients.

This is why as MSF we seek to negotiate with all parties to a conflict. It’s to enable our teams to deliver assistance when it is needed most. Often these moments are in the midst of changes in power and control. It’s also the reason we resist efforts to incorporate our activities into political processes of nation building. It is why we speak out loudly when our facilities and staff are harmed.

The future of Afghanistan is uncertain, and our activities will remain under pressure. The challenges we face will evolve, and the security of our teams and patients remains a concern. But to weather future storms in Afghanistan, humanitarian actors would do well to firmly plot their own course based on the needs that exist, rather than being steered by the changing political winds. Our work can save the most lives when we are able to be as independent as possible.

Christopher Stokes is a senior humanitarian specialist at MSF. He was the head of mission for MSF in Afghanistan in 1996 when the Taliban took over Kabul for the first time and has returned regularly to the country over the past two decades to support and represent MSF operations in his capacity as the director of operations and the general director of MSF’s Operational Centre Brussels. He was most recently in Afghanistan in 2021.

Jonathan Whittall is the director of the analysis department at MSF. He helped set up the Kunduz trauma hospital as a project coordinator in 2011 and 2012. He has also returned to Afghanistan on multiple occasions, including to carry out research on access to health care in Helmand province as a senior humanitarian advisor, and to support the teams in negotiations in Kabul after the attack on our hospital in Kunduz in 2015.