Mexico/New York, June 20, 2018—New asylum rules and policies imposed by the United States government are cruel and inhumane, and deny safety to thousands of Central Americans fleeing extreme violence, said the international medical humanitarian organization Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) on Wednesday, World Refugee Day.

The Trump Administration is now effectively dismantling protections enshrined in US and international law designed to protect refugees and asylum seekers. US authorities are subjecting people who have been the victims of crime, torture, and abuse to even greater harm and suffering—including detaining and forcibly separating children from their families.

"Seeking safety is not a crime," said Jason Cone, executive director of MSF-USA, who recently visited MSF programs in El Salvador. "People arriving at the border have been victims of gang violence and abuse, only to be treated now like criminals by US authorities. The Trump Administration is demonizing vulnerable people who most need protection and care, and by doing so is joining the ranks of the very abusers our patients are fleeing."

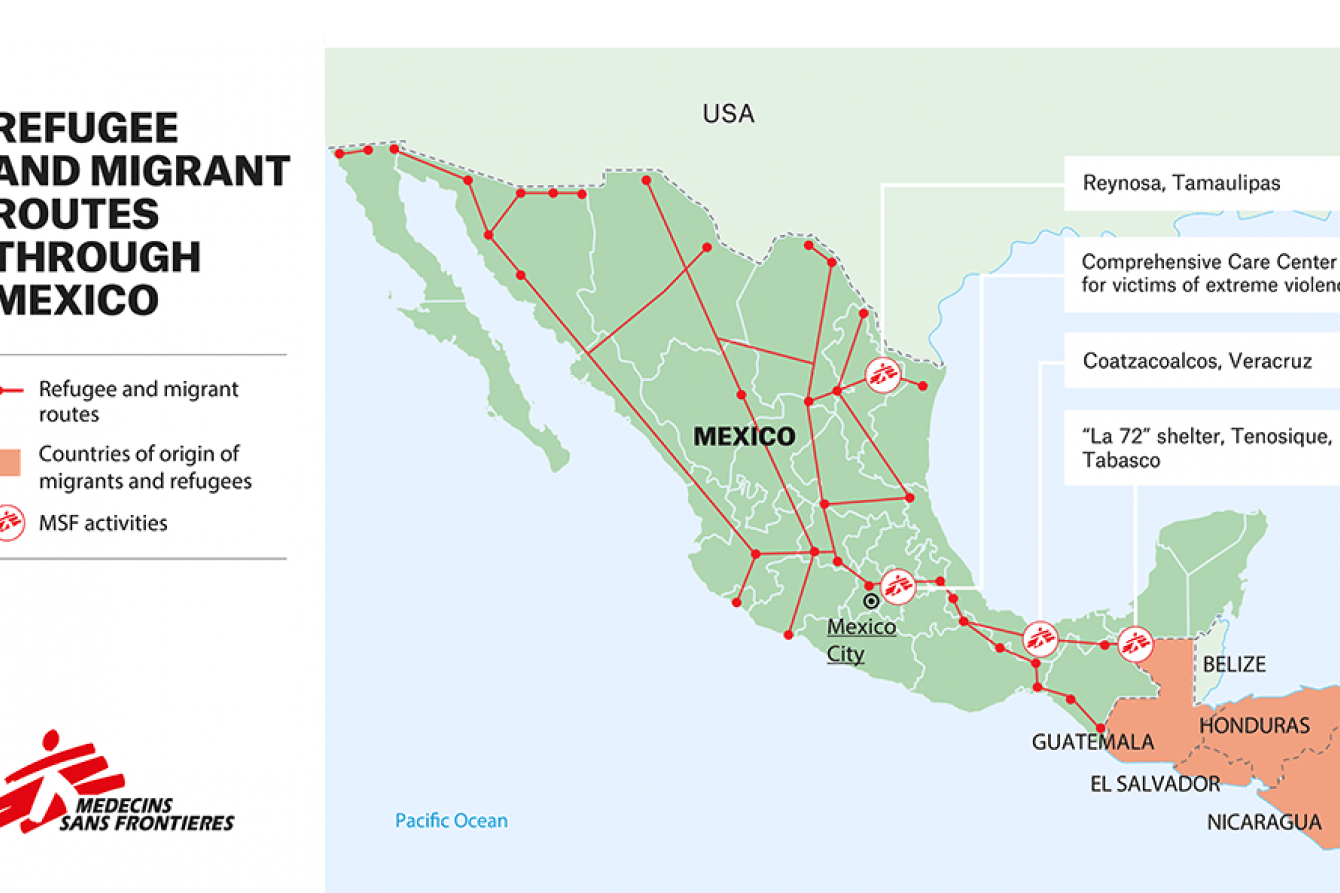

Since 2012, MSF has been providing medical and mental health care in mobile clinics along Mexico's migratory routes toward the United States. Patients describe escaping relentless violence in their home countries. They've survived the death of family members, assault, kidnappings, extortion—both at home and along the migration route. The violence they have endured and the mental trauma they carry are similar to what MSF witnesses in war zones.

Every year, more than half a million people flee El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. In survey and medical data from MSF’s programs in Mexico released last year, 55 percent of Salvadoran refugees and migrants reported being victims of blackmail or extortion, 56 percent had a relative who had died due to violence, and 67 percent said they never felt safe at home. In total, 92 percent of the 1,817 migrants and refugees treated by MSF mental health teams in previous years had lived through a violent event in their country of origin or during the route.

Last week, US Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a ruling that survivors of gang and domestic violence would no longer have grounds to apply for asylum in the US—a sweeping decision that would close the door to most people fleeing threats in Central America. Earlier this year, the Administration revoked Temporary Protected Status for hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans and Hondurans living in the United States, ignoring their security concerns.

These policies targeting Central American migrants are part of a cruel strategy—including the separation of parents and children at the border—designed to deter families from attempting to seek asylum in the US and to limit refugee admissions at a time of record levels of forced displacement worldwide.

"No other government in the world is deliberately and systematically separating refugee children from their mothers and fathers as policy," said Cone. "This is an abhorrent, abusive practice that must end immediately before more harm is done to these children. However, ending the policy of family separation is not enough. It is the bare minimum needed to protect asylum seekers and refugees. We must also demand an end to so-called 'zero tolerance' rules that criminalize asylum seekers and recognize that many people fleeing parts of Central America have a credible fear of death, violence, or persecution if they are deported."

The ongoing instability in Central America has greatly increased the flow of migrants and refugees in 2018. MSF in Mexico is seeing the largest influx of migrants in shelters where the organization works, particularly women, unaccompanied minors, and families. In the first four months of 2018, the La 72 shelter in Tenosique, Mexico, registered 4,863 people, an increase of 93.5 percent, compared to the same period in 2017. Last year, 90 percent of those assisted by MSF psychologists in three of MSF’s migrant shelters said they had suffered intentional violence, either in their home countries or during their journeys through Mexico. This trend has continued in the first four months of 2018.

Away from the US border, continued instability in Central America and new US policies are trapping people in Mexico and transforming this transit country into a forced final destination for thousands of vulnerable refugees and migrants. Violence in Mexico is widespread and heavily affects Central American communities on the move. Gangs maintain a strong presence across parts of Mexico and are responsible for many attacks against migrants. Migrants face grave risks of kidnapping, disappearance, sexual assault, trafficking, torture, and direct violence in Mexico.

"Mexico is not well-equipped to protect refugees and migrants, or to offer them adequate humanitarian assistance," said Marc Bosch, MSF head of operations for the region. Migrants and refugees desperate to find safety are often easy prey for criminal networks that offer to help them cross the border but also abuse them," he said.

"Both the US and Mexico need to reform their protection policies to improve access to health care and uphold human rights," said Bosch. "It is not acceptable to force migrants and refugees to choose between facing the threat of death in Central America and Mexico or the separation of their family and loss of freedom in the US."

Since 2012, MSF has been providing medical and mental health care to migrants and refugees from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador moving along the migratory route through Mexico. MSF has adapted its intervention strategy as the migration crisis has evolved—from the work carried out in migrant shelters and mobile clinics along railway lines, to the work established in several locations on the migrants' route (in Tenosique, Coatzacoalcos, and Reynosa, Mexico). MSF also runs a Comprehensive Care Center for victims of extreme violence in Mexico City. This center opened in 2016 as part of a strategy to respond to the medical and humanitarian needs of people in transit.