Chéride Kasonga has just returned from Pibor, Africa, one of the neediest regions of perpetually conflicted South Sudan. From March to September 2016, Kasonga a doctor from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), worked at a referral health center supported by Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). For him, going on a mission with the organization is a way of fulfilling his belief in quality medicine for everyone.

"In my country, I came up against the reality of an unsubsidized health system that requires that patients themselves pay the cost of their health care” says Kasonga. “So it was difficult for us to provide care to those who did not have financial resources and thereby to respect the Hippocratic Oath that requires every doctor to make the health of their patients their priority. That is why I chose to work with MSF in order to be able to freely and with a clear conscience, practice the medicine that I learned."

Since 2007 Kasonga has had a major role working on MSF projects in the DRC including the towns of Kisangani and Niangara. His involvement with the organization later brought him to other regions of Africa in need of care. He spent time in northern towns of Mali and Mauritania, and the Central African Republic. Most recently, Kasonga was stationed in South Sudan on a six-month assignment.

"I worked for eight years in my country. I have friends who stayed there, who are with their families and earn more money than I do. But working outside DRC allowed me to gain many valuable experiences,” Kasonga explains. “As a doctor, it is important to know your patient, their way of living, their dietary preferences, and their beliefs in order to treat them adequately. This ability that I gained, among others, made me more human in practicing my profession. In addition, working in places where people really need your help is very important to me, even if it can sometimes involve risks."

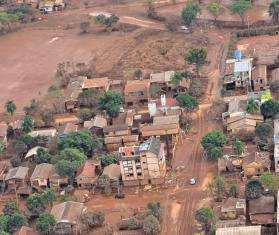

Kasonga was the only doctor working at MSF’s referral centre in Pibor, South Sudan. This MSF project aids a population of some 170,000 people who have no other access to health care in the country. Between April and July 2016, the center held 19,488 outpatient consultations and more than 230 inpatient consultations.

Work days at the project site involve many tasks. Congolese doctors like Kasonga are responsible for supervising activities and administrative tasks while tending to the clinical care of patients and staff training. The day can feel like an endless marathon, but providing free services to a population that has no access to medical care gives Kasonga a level of gratification that makes it all worth it.

"We sometimes experience great difficulty in reaching some health posts,” says Kasonga. “In the rainy season, the roads are impassable, and the water in the rivers is sometimes not deep enough for a dugout to navigate on. In that situation, these health posts cannot refer seriously ill patients to Pibor. But when you arrive to provide care and restore an appetite for life, the smiles of the patients or their relatives do you a world of good.”

A Risk Worth Taking

The work Kasonga does with MSF throughout the DRC and elsewhere often places him in situations of unstable security. But even the dangers of working in the field have never blurred his commitment to helping the many people in need of medical care.

"My enthusiasm for humanitarian work has never been extinguished," Kasonga says.

Beyond the humanitarian concerns caused by insecurity, Kasonga lacks confidence in the medical treatments provided outside of MSF facilities for common serious conditions in the region.

"That resulted in many people coming to us in a very degraded state of health because they had for a long time put themselves in the hands of unqualified practioners or had taken substances for a long time whose toxicity they were unaware of, whereas we were providing quality care, free of charge,” Kasonga explains.

Malaria, diarrheal and respiratory infections are some of the recurrent conditions treated at the referral center in Pibor. But other cases caused by violence also made an impression on Kasonga.

"Once, a young man of 25 was brought to us in a state of mental confusion and with multiple deep wounds, on the head, the back, the arms, and the legs. He had been hit with a machete by members of the family of a girl with whom he was going out. He had lost consciousness for about 24 hours before waking up and remaining confused for several days,” says Kasonga. “We admitted him and treated him. We were very pleased to see him leave the hospital having recovered his physical and mental capacities after 45 days of hospitalization."

Kasonga is back in the DRC where he is happy to be with his family after a long time spent away from home. Still, Kasonga cannot silence his passion for responding to the needs of others. He says he can barely conceal his impatience as he waits for the next opportunity to work alongside MSF where he can continue to reach his mission: to save lives, at any cost!