Three MSF staff members give first-hand accounts of the months they recently spent inside Syria caring for wounded patients in a clandestine surgery program.

2012 © Google

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been working on the ground in Syria for the past two months, trying to provide humanitarian assistance to people affected by the conflict. With the help of a group of Syrian doctors, in six days a team was able to transform an empty house into an emergency hospital where wounded people could be operated on and hospitalized.

As of mid-August, MSF had admitted more than 300 patients to this facility and carried out 150 surgeries. The injuries have been largely conflict-related. Most were caused by tank shelling and bombing. Many patients had suffered gunshot wounds. The majority of the patients have been men, but up to one in ten are women, and approximately one in five are under the age of 20. According to the medical team, two-thirds of the procedures carried out were emergency surgeries.

However, the future of the project is uncertain. In addition to the fact that MSF is working without authorization from the Syrian authorities, our activities are under threat by the changing nature of the conflict, difficulties accessing supplies, and the challenges the wounded face in reaching the hospital.

Considering the levels of violence in Syria today, the MSF team, which is made up of national and international staff, can only provide a limited amount of medical support. This assistance is nonetheless essential for the survival of the people treated at the hospital.

For the people who speak out in this package, the patients and the kinds of wounds that they were treating are evidence of the use of heavy artillery and, more broadly, a war that is not sparing civilians.

"Some [Were] Arriving Too Late to be Saved"

Kelly Dilworth

Kelly Dilworth, an MSF anesthetist who has worked for MSF for nine years, spent one month on mission in Syria. She recalls the pain of the wounded people she was treating and the severity of their injuries in a context where it’s difficult to get appropriate care in time.

I arrived a short time after MSF started treating people and was [thereafter] involved in about 100 operations. Ninety percent of these surgical procedures were for injuries linked to violence, predominantly from explosions and shelling. We were also seeing a significant number of gunshot wounds. However, the victims of heavy artillery were particularly striking because of the scale of their injuries, the extensive fragmentation wounds caused, and the fact that civilians are indiscriminately involved.

Given the hospital’s capacities, the arrival of even a small group of severely injured patients was enough to threaten to overwhelm us. In these situations we had to pull out all the stops, multiply our efforts, and literally multiply ourselves . . . Along with others in the team, I worked in the emergency room, operating theater, and post-operative wards. Simply resuscitating and operating on injured people does not mean the job is done. We also need to ensure that we give the best post-operative care possible: good analgesia, intensive care for critically ill patients, deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, nutrition, etc.

On arrival the injured were often in terrible pain, with all its consequent risks. We were seeing patients with stiff limbs and joints, mobility problems, and serious respiratory complications.

Some came from far away, having travelled up to 150 kilometers [about 93 miles] to reach us. A good number arrived long after the initial injury had occurred rather than in the acute or semi-acute phase, [with] some arriving simply too late to be saved. Among them were patients who had not been able to have any post-operative care after their surgery, patients who received inadequate care and others who hadn’t received any medical care at all.

One 14-year-old boy was admitted with respiratory failure and fluid overload. He had had a laparotomy and splenectomy [removal of the spleen] and was in a really bad way, having not been able to have timely and adequate care. He arrived literally “frozen” in position on a stretcher, but happily left smiling a few days later.

I also remember another wounded person in a terrible state when he was admitted. He had been operated on several days beforehand but had to flee immediately after the operation because there was a threat of bombing in the area. It had taken him two or three days to get to our hospital. He also pulled through.

These delays aggravate the problem of infection. When you’re dealing with a bullet or shell wound, you need to prescribe antibiotics and not close the wound in the first instance. A secondary closure should be done three to five days later, the exact timing according to the case. Well, many of the injured people we saw couldn’t get proper care because of a lack of available resources in and close to the areas where the fighting was going on. This results in serious complications. A 15-year-old adolescent arrived in septic shock due to a traumatic intestinal perforation. He had been injured two days before by a tank shell and hadn’t received surgical care. In such cases, the cascade of complications triggered in the body can rapidly carry off the patient. In spite of the surgery and all the intensive care we had to offer, he died two days after the operation.

"We're Getting Good Results"

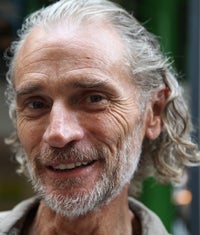

Brian Moller

Brian Moller is an anesthetic nurse. He has been working with MSF for nine years and is today an emergency coordinator. This July, Brian managed the surgical hospital set up by MSF in Syria.

What’s your point of view on what is happening in Syria?

We’re working in a rebel enclave and thus only have a partial view on the entire situation. It’s a war though—one that doesn’t spare civilians. Some are targeted by snipers and others are victims of “collateral damage,” as they say. Whereas regular army troops were confronting demonstrators in the past, they’re now clashing with armed opposition groups, mostly in urban centers. From what we are seeing, these groups are varied, made up of people with different social backgrounds and grievances. The only thing that they all seem to have in common is their anger towards the Syrian regime.

As an NGO, isn’t it complicated to work only on one side?

As we don’t have official authorization to work in the country, we don’t have a choice. Our work consists of coming to the aid of those who don’t have access to health care. The supporters of the regime can access public hospitals, but many of the rebels and their supporters are deprived of this access and assistance. We also explain to people that the causes of this violence are less important to us than its consequences from a medical point of view. And though we are working in rebel territory, we insist upon the fact that we make no distinction between supporters and opponents of the regime in administering care. Our position is relatively well understood from an intellectual standpoint by the health professionals and Syrians we meet. It’s not as well understood from an emotional point of view. Since the beginning of the Syrian uprising, many have had people close to them get injured or killed.

How are Syrian health professionals dealing with the situation?

Their availability and willingness to help each other out is impressive, given the context. They are not experienced or prepared for such an influx of patients, or for treating these types of injuries. Our team’s experience in this regard reinforces the abilities of the local staff, who are seeing this kind of violence for the first time. We’re dealing with it, and we’re even getting good results in spite of the difficulties and ethical dilemmas that arise. For example: what are the priorities? When can one say that there’s nothing more that can be done for a patient? When does one stop aggressive therapy? There are many questions that create tensions and heated exchanges between staff confronted with the demands of rationality in an extremely emotional situation.

What are health and medical services like in the region in which you’re working?

There are dispensaries, pharmacies, and places where consultations are carried out, but there is no capacity for surgery and hospitalization in this area. Further afield, hospitals that are able to operate on people refer them to us so that we can hospitalize them post-intervention. Getting medical supplies and medicines is also a problem. Blood, painkillers, anesthetics—they’re short on everything. Along with access to water, electricity, and communication networks, these problems of availability, transport, and supply are particularly acute, though they pose a problem in all conflicts. On our side, we are succeeding thanks to a group of Syrian doctors and the efforts of our logisticians in maintaining a buffer stock that permits us to hold out two weeks in case of any major problems. We are also getting private donations, which attests to the solidarity of the people around here. A few days ago, some women from the village arrived with two big bags full of medical and dressing supplies and medicines purchased from the local pharmacies. Where these products came from originally is hard to verify; for example, if you don’t know where anesthetics drugs came from, can you use them? The problem in a context of war is that you don’t always have the choice.

"Injured People Started Coming from Everywhere"

Anna Nowak

Surgical specialist Anna Nowak has completed more than 20 missions with MSF. She has just returned from Syria, where she helped to set up the project.

How did you manage to set up this emergency mission without official authorization from the Syrian authorities?

With the support of a group of Syrian doctors, we were able to identify a location to perform operations. After an initial brief visit, we decided on an empty villa. The two-story, eight-room house was still under construction, but we didn’t have any other choice. For six days, we worked like crazy to transform the place into a surgical hospital with a dozen hospital beds, a sterilization room, an operating theater, a resuscitation room for emergencies, and a recovery room. In addition to the difficulties involved in recruiting medical staff locally, we also had to solve supply problems, knowing that it’s risky right now to import or to buy medical supplies in Syria.

In what kind of conditions did you start operating on people?

The first patients arrived on June 22, the day after the hospital opened. At first, we admitted mostly injured people who already had undergone surgery. Unfortunately, we had to do this under poor hygienic conditions, which generally means a higher risk of infection. As new conflicts broke out, the hospital quickly reached its limits. After a few days, we were getting up to six injured people at a time, a relatively modest number but still high considering our resources and treatment capacity. Then, injured people started coming from everywhere. We had to come up with other ways of accommodating people, even if it meant putting beds on the terrace. Sometimes the wounded didn’t arrive during the day because of fighting, because the roads were blocked, or because traveling to the hospital was risky. Sometimes they came at night or at dawn. It was tiring, even though we could count on the help of the patients’ caretakers. The openness and willingness of these people to help out was really touching.

What kinds of injuries have you been seeing?

We’ve largely been seeing people wounded by bullets, mortar fire, or shells. The most common injuries have been to people’s limbs, stomach area, or between the neck and abdomen. Though most of the patients are men, women and children have also been arriving, and often too late. At the moment, there is fighting and bombing about ten kilometers [about six miles] from our facility. But our patients sometimes came from far away, risking their injuries becoming worse or even death. This makes you wonder about what hurdles stand in the way of getting quality care in Syria today, including for people whose wounds are not conflict-related, such as people injured in road accidents.

What are the main difficulties involved in such an intervention?

To limit the risks, hospital staff in Syria are working in a discreet and cautious manner, and many of the field hospitals disappear as quickly as they appear. In this context, the existence of a facility like ours is very important for injured people who need assistance, but it is also a very delicate situation. Security constraints limit our resources and capacity. A typical war wound requires an average of five days of hospitalization. With the exception of the most serious cases, we sometimes have difficulties keeping patients in hospital longer than this. Patients who live close to the hospital or who are staying with family and friends nearby can come back for checkups or to get a dressing. But even though there’s lots of solidarity among the people here and lots of patients are able to stay in the area temporarily, some leave the hospital and we never hear from them again.

Aside from the surgical project, MSF is distributing drugs and other medical supplies in Syria. Despite the difficulties accessing the country, MSF remains ready to assist all victims of the conflict and we continue to expand our activities in Syria and neighboring countries. At present, MSF is admitting about 50 injured Syrians a month to our reconstructive surgery project in Amman, Jordan. We are also offering psychological support and primary care to Syrian refugees in Lebanon. MSF’s 2012 budget for Syria-related activities is currently estimated at more than €5 million [more than $6 million].